The Fair way to do marketing

Advertising in the Web3 Era

The Fair way

to do marketing

in the “Privacy Age”.

Facebook probably has your phone number, even if you never shared it. Now it has a secret tool to let you delete it.

Shona Ghosh Oct 31, 2022, 4:58 AM

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Stephen Lam/Reuters

- Facebook almost certainly has your phone number and email address, even if you never handed them over.

- That’s because any friend who shared their address book with Facebook also shared your details.

- Now the firm has a new tool to let people check if Facebook has that data, and delete it.

Facebook’s parent firm Meta has quietly rolled out a new service that lets people check whether the firm holds their contact information, such as their phone number or email address, and delete and block it.

The tool has been available since May 2022, Insider understands, although Meta does not seem to have said anything publicly about it.

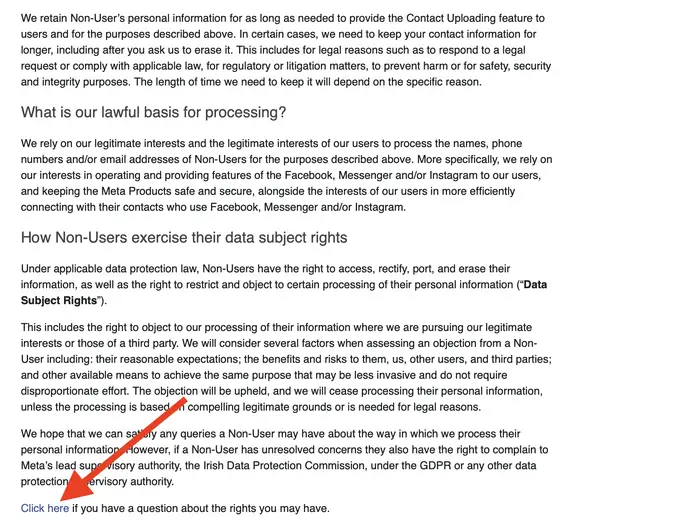

A tipster pointed us to the tool, which is well-hidden and apparently only available via a link that is embedded 780 words into a fairly obscure page in Facebook’s help section for non-users. The linked text gives no indication that it’s sending you to a privacy tool, and simply reads: “Click here if you have a question about the rights you may have.”

Meta has buried its new contact-blocking tool 780 words into an obscure help page. Meta/Shona Ghosh

Here’s how the contact-blocking tool works

Once you have actually found the contact-blocking tool, it’s pretty straightforward.

The company explains that even though you may not have signed up to use any core Meta service — such as the Facebook app, Messenger, or Instagram — it may still have your contact information.

For many years, the firm asked users signing up for any of its apps to share their phone contacts, with the stated goal of helping them find friends. A side effect is that Meta, whose combined apps boast almost 3 billion daily users, has amassed an unknown but likely vast amount of personal contact information for people who have never signed up for an account, nor opted to share their information.

The tool, in theory, allows a non-user to mitigate some of this damage. And although the tool is targeted at people who have never signed up for Meta’s apps, it’s likely also useful to anyone who is a user but never wanted to share this information.

Enter any number or email you want to check

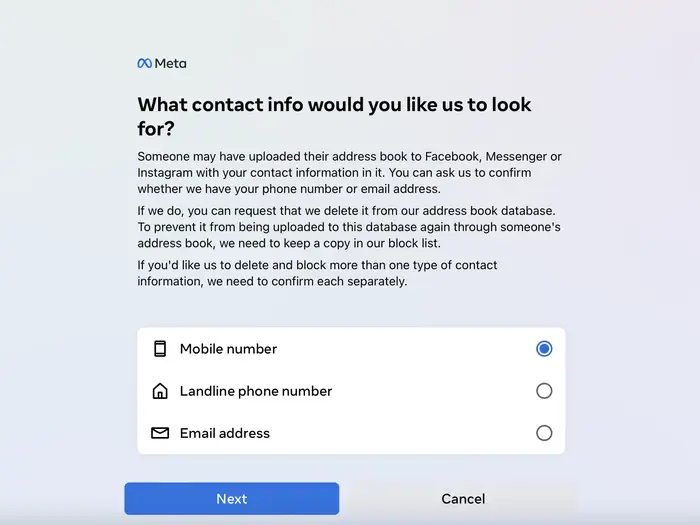

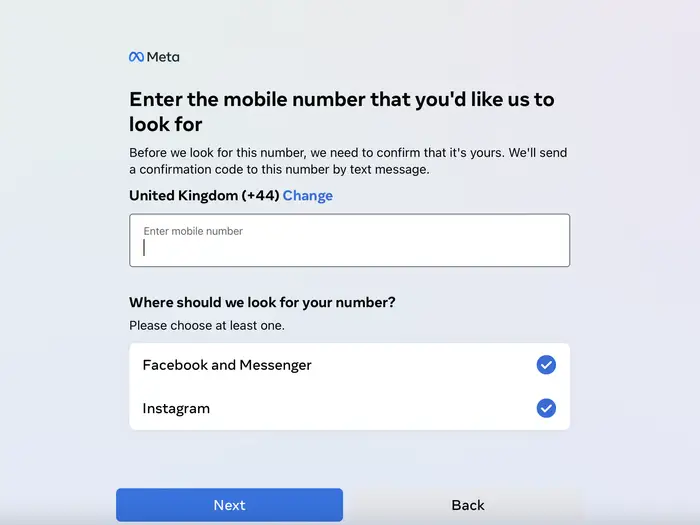

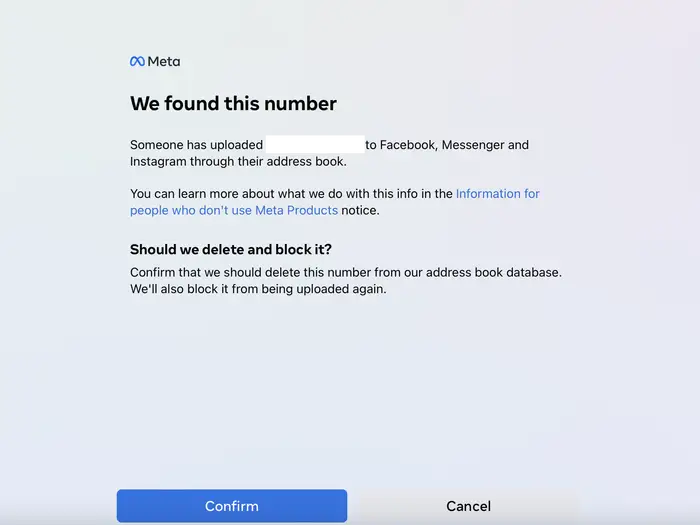

The service asks whether you want to scan for a phone number, landline number, or email address that may have been uploaded by a friend who uses Meta’s core apps: Facebook, Messenger, or Instagram.

“You can ask us to confirm whether we have your phone number or email address,” the firm states. “If we do, you can request that we delete it from our address book database. To prevent it from being uploaded to this database again through someone’s address book, we need to keep a copy in our block list.”

Meta declined to answer questions from Insider about how its block list works.

You can enter any contact details you think may have been uploaded to Meta’s services.

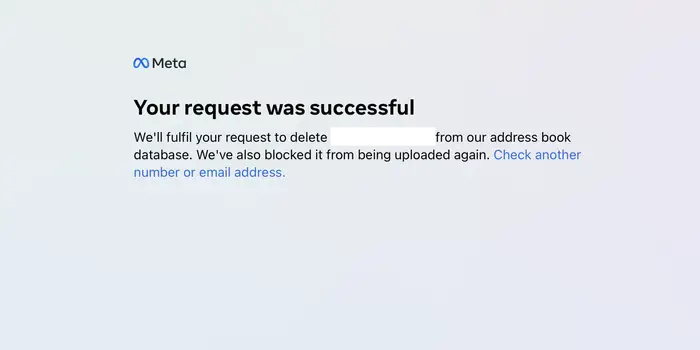

It takes a few seconds to scan for that data and, if it shows up, Meta will ask if you want that contact information blocked.

Meta’s contact-deletion tool Meta/Shona Ghosh

Meta’s contact-deletion tool Meta/Shona Ghosh

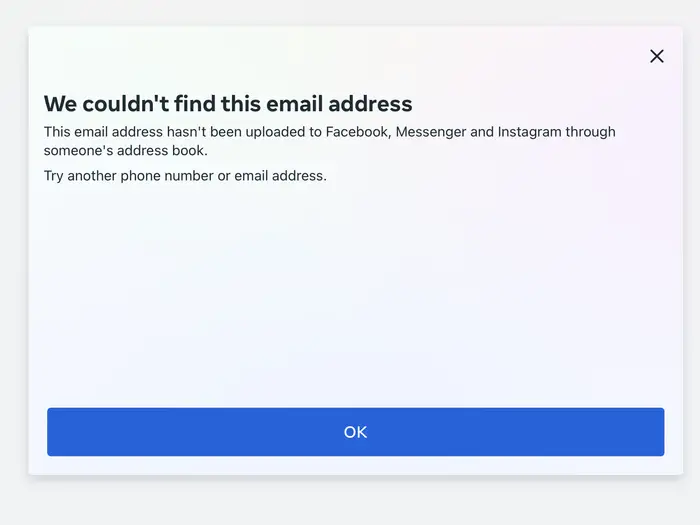

And here’s what it looks like if Meta doesn’t hold your data on its servers.

The bad news: It’s a drop in the ocean of what Meta has on you

Figuring out the benefits of doing any of this requires a bit of intellectual reverse-engineering. A primary benefit is privacy and the knowledge your data won’t contribute to the opaque power of Facebook algorithms, such as its infamous “people you may know” feature.

It also gives more control to people whose data has been directly affected. Up until now, Meta only allowed users who had uploaded their contacts’ data to delete that information.

But in reality, privacy experts told Insider, deleting and blocking this small amount of data is one drop in the ocean compared to what else Meta has on you, regardless of whether or not you use its apps.

For example, Meta harvests information on what people do outside its apps through Pixel, a piece of code that tracks what they do on different websites. That the firm has both browsing data and phone numbers of people who don’t even use its services has given rise to the concept of “shadow profiles.”

“We first heard about shadow profiles very early in Facebook’s dominance,” Heather Burns, author of the book “Understanding Privacy”, told Insider. “Facebook was keeping a sort of profile on you, even if you didn’t have a Facebook account, composed of data gathered through things like Facebook Pixel.

“Parallel to that was this notion of uploading the contact book, which at various times in Facebook’s history was enabled by default when you started an account,” she added. “Even if you were a privacy-conscious person, if you hit that button, you had uploaded your friend’s data. It feeds into the shadow profiles of people whether or not they use the service at all.”

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg appeared ignorant of the term “shadow profiles” during Congressional hearings in 2018, but admitted the firm collects data on non-users.

Burns says she has never signed up for a Meta-owned service but found, on trying Meta’s new privacy tool, that her email addresses and phone number had been picked up by the company. “It’s all in there, even though I’ve never had an account,” she said. “I don’t believe anybody uploaded my data to Facebook in a malicious manner, I’m just in someone’s address book.”

But, she says, while it’s positive that Meta now lets you block this information, “that’s just two strings of data.”

“I still have to use a browser with multiple defense plugins to protect myself from Meta on every page I view,” she added. “They are still tracking people, by default, even if they don’t use an account. The notion that there’s a tool to remove two data strings, to me, it’s both beneficial and laughable.”

Meta declined to answer questions from Insider about why it has rolled out this new tool, and why this year.

Meta may use this tool as a regulatory defense

Both Burns and Eerke Boiten, professor of cybersecurity at De Montfort University, speculated that the motivation could be political or legal as regulatory scrutiny of the major tech firms increases.

“There are two things — one is that installing the Messenger app leaks all of your contacts, that’s an undeniable invasion of privacy,” said professor Boiten. “But now if anybody brings that up, Meta can always say: ‘It doesn’t have to be like that, you can undo the damage.'”

The second reason may be WhatsApp, which was bought by Meta in 2014 and whose core messaging functionality relies on people uploading their contact data to the app. An ongoing battle between Meta and regulators is whether it can connect the data it sucks up through WhatsApp to its other apps.

“Having the possibility to delist your number from Facebook in a way that it can’t be used by Facebook to make friend suggestions would be an argument that ‘OK, we can do this safely,'” said Boiten. “It wouldn’t be very transparent … the friend-suggestions algorithm is one of the least transparent of all, so it would be difficult to establish in any way that delisting a phone number would make an impact.”

It’s possible that Meta isn’t really technically deleting your phone number and emails at all, said Boiten.

“The way Facebook has organically grown, it’s probably true that the way they store information on people is on all sorts of disparate siloes,” he said.

“It may well be that they only implement something like this on the outside — so at a point the phone number threatens to go outside the system, it says, ‘This phone number is one we’ve been told we can’t use,’ rather than really removing information.”

Although both Burns and Boiten welcomed Meta taking tentative pro-privacy steps, Burns described it as “a classic American approach” that involves scooping up data without asking, versus the more permission-based approach favored by European privacy regulators.

“To me, the Facebook tool is privacy labor,” she added. “They collected data they should not have collected in the first place, and are now shifting responsibility on you to remove it.”

source: www.businessinsider.com